Hotel of the Heart | Le Violon d’Ingres | Il Facchino di Venezia (The Porter of Venice) | Green Nights / Golgotha / Love’s Quarrel | Alogon | Stone Dragon Bridge | An Earring Depending from the Moon | The Fishmonger’s Door | Circus in the Fog | Small China Moon | Eastern Shadows | Keats Dying in Your Arms | With Grass Ropes We Dragged the World to Her in Wooden Boats | Where Angels Arch Their Backs and Dogs Pass Through | Frost Heaves | Like Branches to Wind | A Prayer in a Wolf’s Mouth | Road Narrows: Poems of Tunisia | A Tattoo in Morocco | Storyville | Ghost Stations | One Thing at a Time | Oracle Bones | Night Song of the Cicadas | Scenes of Everyday Life | Bamboo Ladders | Desuetude | More Fugitive Than Light

These publications are available either through

1. the individual publishers; 2. Amazon.com 3. edgewisepress.org;

or directly through 4. jlglass@mindspring.com

Hotel of the Heart: Poems 1997-2001

(Pavia, Italy: Night Mail, 2002)

Le Violon d’Ingres:

Sunday Poems and Lineations 1993-1996

(Bomarzo, Italy: Night Mail, 2004)

Along the Hudson

(Tokyo, Japan: Tokyo Publishing House, 2006)

Mute Sirens:

A Suite of Poems for Carlo Benvenuto

(Modena, Italy: Emilio Mazzoli Editore, 2007)

Il Facchino di Venezia (The Porter of Venice):

Poems 2002-2003

(Venice: Sotoportego Editore, 2007)

Green Nights / Golgotha / Love’s Quarrel:

Poems 2001-2003

(Belgrade, Serbia: Dossier, 2007)

Alogon:

Early Poems, 1969-1981

(Tokyo, Japan: Tokyo Publishing House, 2007)

Stone Dragon Bridge: Poems of China 2006-2007

(Modena, Italy: Emilio Mazzoli Editore, 2007)

An Earring Depending from the Moon:

Poems 2006

(Venice: Sotoportego Editore, 2008)

The Fishmonger’s Door:

Poems of Modena 2000-2008

(Modena, Italy: Emilio Mazzoli Editore, 2009)

Circus in the Fog: Poems 2005-2006

(Venice: Sotoportego Editore, 2009)

Eastern Shadows: Poems of Romania 2008-2009

(Craiova, Romania: Scrisul Romanesc, 2010)

Small China Moon: Poems 2002

(Pasian di Prato [Udine], Italy: Campanotto Editore, 2010)

Keats Dying in Your Arms:

Poems 2007-2008

(Brussels, Belgium: Éditions Passage St.-Hubert, 2010)

With Grass Ropes We Dragged the World to Her in Wooden Boats:

Poems of Jordan, Syria, and Egypt, 2008

(Cumiana, Italy: Libri Canali Bassi | Paolo Torti degli Alberti, 2011)

Where Angels Arch Their Backs and Dogs Pass Through:

Poems of India and Nepal 2010-2011

(Craiova, Romania: Scrisul Romanesc, 2012)

Frost Heaves: Poems 2008

(Cumiana, Italy: Libri Canali Bassi, 2013)

Like Branches to Wind: Poems 2008

and

A Prayer in a Wolf’s Mouth: Poems 2013-2014

(Turin, Italy: Lower Canal Books, 2014)

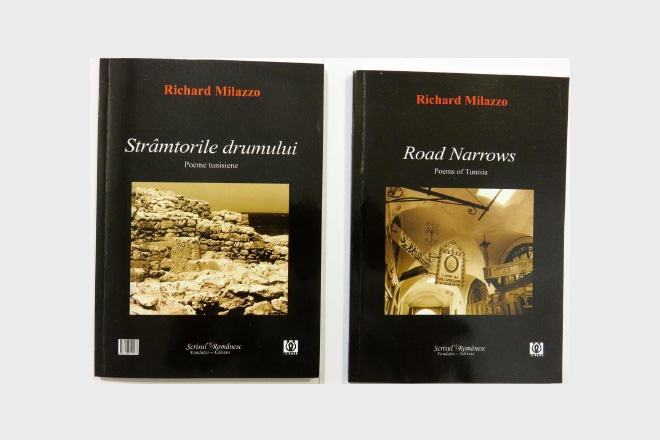

Road Narrows: Poems of Tunisia

(Craiova: Scrisul Romanesc, 2014)

A Tattoo in Morocco: Poems 2010

(Modena: Edizioni Galleria Mazzoli, 2015)

Storyville: Poems 2007

(Hayama and Tokyo: Tsukuda Island Press, 2017)

Ghost Stations: Poems 2015-2016

(Hayama andTokyo: Tsukuda Island Press, 2017)

One Thing at a Time: Poems of Japan, 2016

(Berlin, Germany: Galerie Albrecht, 2017)

Oracle Bones

(Hayama and Tokyo: Tsukuda Island Press, 2018)

Night Song of the Cicadas: Poems of South Korea, Japan, Vietnam, Cambodia 2017

with drawings by Joel Fisher (Berlin, Germany: Galerie Albrecht, 2018).

Scenes of Everyday Life: Poems of Vietnam, Indonesia, Cambodia, Russia, 2016

with mixed media works by Aga Ousseinov (Hayama and Tokyo: Tsukuda Island Press, 2020).

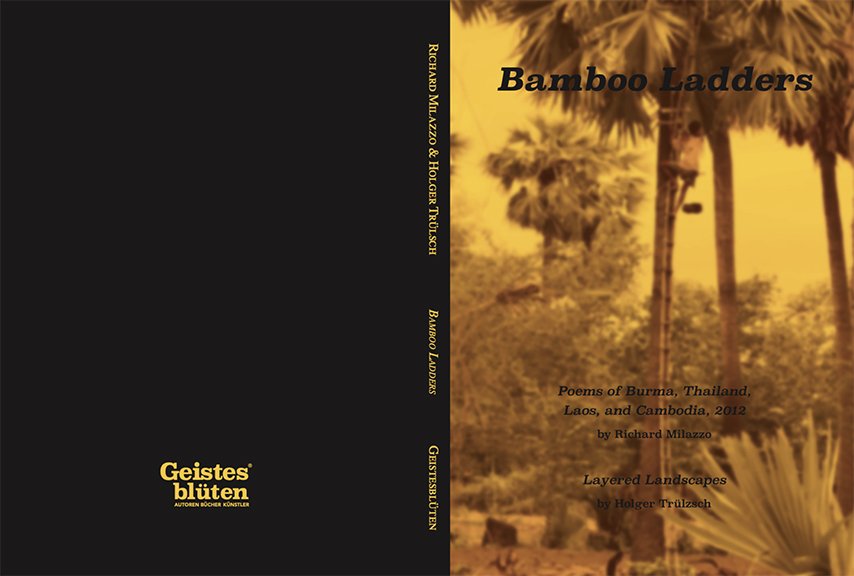

Bamboo Ladders: Poems of Burma, Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia, 2012

with drawings (Layered Landscapes) by Holger Trülzsch (Berlin: Edition Geistesblüten, 2022).

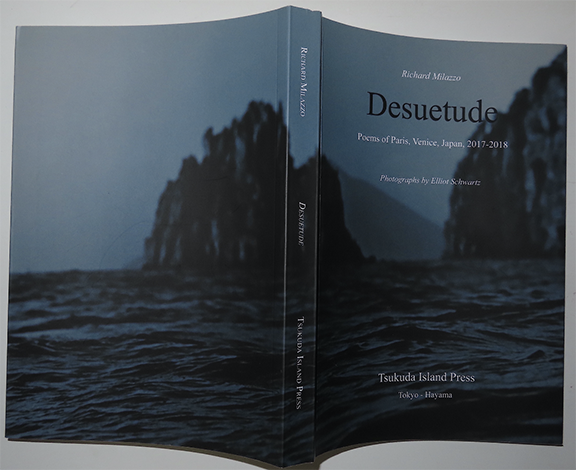

Desuetude: Poems of Paris, Venice, Japan, 2017-2018,

with photographs by Elliot Schwartz

(Hayama and Tokyo: Tsukuda Island Press, 2022).

“More Fugitive Than Light: Poems of Rome, Venice, Paris, 2016-2017

with collages by Daniel Rothbart

(Tokyo - Hayama, Japan: Tsukuda Island Press, 2024).

Hotel of the Heart: Poems 1997-2001

Richard Milazzo

With an Italian translation by Nanni Cagnone.

First edition paperback: December 2002.

96 pages, with the cover photograph by André Kertész, Martinique, January 1, 1972,

and a black and white photograph of the author by Michel Frère on the frontispiece,

7.25 x 4.75 in., printed, sewn and bound in Turin, Italy.

ISBN: 88-88454-06-3.

Pavia, Italy: Night Mail, 2002.

Written mostly in Paris, Greece, and Italy (the book was published in Italy and is, in fact, accompanied by an Italian translation) during a four-year period, in three, four and five line stanzas, Hotel of the Heart: Poems 1997-2001 by Richard Milazzo speaks of the soul in extremely disciplined forms. There is a sadness about this author’s second volume of poetry (his first was Le Violon d’Ingres: Sunday Poems and Lineations 1993-1996) that seems to reflect a state of mind or being that inheres naturally to the act of writing poetry.

About the poems in Hotel of the Heart, the poet and translator Nanni Cagnone writes: “The difficult intonations and the distance this introduces are perhaps those of the impassioned-desolate commentator standing alone before an aurora borealis or an interminably congenital sunset. What we encounter here is the seriousness of poetry.” In keeping with these sentiments, the cover prints an image by André Kertész of Martinque that shows a shadowy figure behind an opaque glass curtain looking out to sea. The black and white photograph of the author on the frontispiece, taken by one of the author’s favorite artists, Michel Frère, who was found dead in his early 30s, a suicide, shows the author on the artist’s boat, where he lived and maintained a studio in New York City when he was not living and working in Belgium. In a poem entitled, “Mycenae,” the poet writes: “Unlike the charging bull of Knossos / Negotiating the champagne maze / Of clinking glass / The eminence of concrete columns / In drawing rooms // Your ancient Minoan existence now / On rocky crag and precipitous hill / Rain and windswept / Amounts to little more than mere inference / Drawn from unkempt boundary stone!”

Le Violon d’Ingres:

Sunday Poems and Lineations 1993-1996

Richard Milazzo

First edition paperback: October 2004.

96 pages, with a black and white photograph of the author by Joy L. Glass, Paris, December 1993,

on the frontispiece, and a portfolio of 8 black and white photographs by the author,

7.25 x 4.75 in., printed, sewn and bound in Turin, Italy.

ISBN: 88-88454-09-8.

Published by Night Mail, Bomarzo, Italy, 2004.

Le Violon d’Ingres: Sunday Poems and Lineations 1993-1996 is Richard Milazzo’s first book of poetry. After a hiatus of twelve years, he returned to writing poetry in 1993. He had written poetry from 1967 to 1981, before he unaccountably stopped. Le Violon d’Ingres is an unacknowledged tour de force, in that it rejects the avant-garde Language-writing principles of his generation (even where traces of it are still present, here and there, in this volume), which had become academic by the time he returned to poetry, even as he attempted to deviate from the Modernist parameters of free verse established by Ezra Pound, embracing abstraction and the lyrical in poetry while still holding on to story and the narrative function. “Mauberley Descended”: “You must kill / to forge Archaia / all that is media-bound / and information-ended. // You must leave / the image senseless / if you are to pound / new meaning ascendant.” This short lyric is manifesto-like in lobbying against “imagism” within the new sound-bite and media-bound culture. Besides “Mauberley Descended,” other seminal poems in the volume are “The Man in a Plain White T-Shirt,” “Classic Anedote,” “A Love Poem,” “Poetry,” “The Ambassador of Dreams,” and “Cimetière de Passy.”

Much of Le Violon d’Ingres was written in Paris, and outside New York City, where the writer lives, and published in Italy. His love of travel will become still more apparent in his later books.

The subtitle, Sunday Poems and Lineations, clearly indicates the writer’s self-doubts and sporadic indecision about his return to writing verse. Nonetheless he remains self-assured throughout the volume, adopting a diverse range of experimental and classical forms.

Le Violon d’Ingres does not shy away from emotion, yet it is disciplined. The literary references are considerable but unobtrusive. And it is equally replete with a sense of gravitas and the absurd, evidenced in both instances by the number of epitaphs the author has written in relation to his own death. “Venice”: “The wind / is a clown / in your closet.”

Green Nights / Golgotha / Love’s Quarrel:

Poems 2001-2003

Richard Milazzo

First edition paperback: February 2007.

Designed by Richard Milazzo.

176 pages, with a black and white photograph of the author by Giovanna Zaccaria,

Garden of the Archaelogical Museum, Palermo, Sicily (Italy), on the frontispiece, and a preface by the author, 7.75 x 5.25 x .5 in.,

gatefold covers, printed, sewn and bound in Belgrade, Serbia.

ISBN: 978-86-7738-046-5.

Published by Dossier, Belgrade, Serbia: 2007.

Published in Belgrade, Serbia, in one volume, what each of these three books of poetry – Green Nights / Golgotha / Love’s Quarrel – by Richard Milazzo have in common is the desire to balance the extrinsic demands of story with the more intrinsic ones of subtle, formal invention, refusing to sacrifice the human dimension to the Modernist, mechanistic fallacy of objectivity. The discursive impulse here, even at its most abstract, parallels the author’s travels from city to city, evolving the ‘hotel poem’ to sustained (stanzaic) form. Green Nights takes place mostly in Mexico, Brittany, and Palermo; Golgotha, in Paris and Marseille; Love’s Quarrel, in Palermo and California. And, in between, we find the author in Corfu, Berlin, Zürich, London, Pineland (New Jersey), and Brussels, in Alexandria and along the Nile, and in New York, and dialoguing with Michelangelo, Pisanello, Goya, Gauguin, Max Jacob, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, and Ibn Hamdîs. Not to mention the poor and the revolutionary leader in Mexico, Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos, and the author’s family in the decadent and dying but still strangely resplendent city of Palermo in Sicily. Enjambment of line and the sentential requirements of subject and object yield to the wider physical and social realities of psyche as place and nature as soul.

“It’s not that narrative, the story,” the author explains, “closes down interpretation; it’s that our powers of description fail us just when we need them most, when we are confronted by even the smallest phenomena of nature. What is description; what is the case if it is not, as Wittgenstein says, something like the totality of facts that gives us the world; what is the slavish imitation the sky and earth if it is not pure awe, affection, thralldom, the astonishment we feel when we are stunned by the realizations of life and the living we have not done and cannot do because it is invariably always too late – too late to capture the moment that is always just before us?”

Il Facchino di Venezia (The Porter of Venice):

Poems 2002-2003

Richard Milazzo

First edition paperback: April 2007.

Designed by Richard Milazzo.

72 pages, with a black and white photograph of the author by Joy L. Glass, Venice, Italy, October 1998,

on the frontispiece, 7.5 x 4.5 in., printed, sewn and bound in Turin, Italy.

ISBN-13: 978-0-9793507-0-2. ISBN-10: 0-9793507-0-0.

Published by Sotoportego Editore, Dorsoduro

and Giudecca, Venice, 2007.

Richard Milazzo, the author of this book of poems, Il Facchino di Venezia (The Porter of Venice), sees the poet in the figure of the porters (facchini) who, at one time, hauled luggage in handcarts and on their shoulders from the Santa Lucia railroad station onto the vaporetti and motoscafi to small and luxury hotels alike, across Piazza San Marco and along Riva degli Schiavoni – simultaneously lightening the visitor’s journey and enabling his first visions of Venice. Viewed as an exploited class, they have, since they were last seen in the 1970s, vanished from the lagoon, calli, and fondamente of the city. But often these lowly, unkempt, ‘dirty-fingernailed’ creatures were the ones who knew the most intimate details of life on the canals and in the sestieri, and they are the ones who remind the author of our poets today – lowest on the pecking order of culture, but, precisely because of this reason, and with nothing left to lose, in possession of an uncompromised will to truth. They are the ones hauling light through the crowds and the darkness in the cities of the East and the West.

“Mute Sirens:

A Suite of Poems for Carlo Benvenuto”

Richard Milazzo

in Carlo Benvenuto: Natura Muta.

With an Italian translation by Brunella Antomarini.

First edition paperback: May 2007.

96 pages, with 13 poems by the author and 30 color and black and white photographs by the artist,

11.5 x 7.5 in., gatefold covers, printed, sewn and bound in Milan, Italy.

Modena: Galleria Emilio Mazzoli, May 2007.

Alogon:

Early Poems 1969-1981

Richard Milazzo

First edition paperback: May 2007.

112 pages, with a black and white photograph of the author on the frontispiece, and a preface by the author,

9 x 6.5 in., printed, sewn and bound in Tokyo, Japan.

ISBN: 978-4-902663-00-6.

Published by Tokyo Publishing House, Tokyo, Japan, 2007.

Alogon (against all reason or logic) was a book slated to be published by Out of London Press in 1980. A year later, the author stopped writing verse. It was not until some twenty-six years later that an opportunity arose to publish them in Japan. Containing all of the earliest works that survived, he decided to add the subtitle Early Poems 1969-1981. Now they are all assembled here, “the ones that got pulled from the fire, for whatever reason, and the mask, and all else, gone, except for the faint scent of the sideshow still in the air.”

The influences clearly visible in Alogon are Mallarmé, Celan, early Modernist painting, and the Language writing of the author’s generation. When he returned to writing poetry in 1993, after a hiatus of twelve years, with the long poem “The Man in a Plain White T-Shirt” (in Le Violon d’Ingres), he defiantly rejected Language writing, feeling that its original avant-garde impulse had become academic, and that it had always been over-intellectualized and too ideological for his tastes. Without abandoning the role abstraction might play in writing, he returned to the semantic and human values of story-telling in poetry, even adopting (and adapting) in a highly deformed or skeletal (posthumous) manner the sonnet form. To the intellectual sorrows of Wittgenstein would be added the still more poignant ones of Anna Akhmatova.

But we can see, even in Alogon, early signs of these tendencies in the formal adoption of two- and three-line stanzaic units, thematic strains of chance playing themselves out against generalized suggestive narrativity, and an overall appreciation for human frailty. Among these frailties the author counted the desire to communicate, not only within the intensive formal boundaries of the lyric but within the seemingly more comprehensive or boundless epic form. Where the short form of the lyric (never less than 3 stanzas of 4-lines each or 12 lines per poem) lent itself to writing in hotel rooms, abstract residues of the epic form reflected his ongoing travels around the world. We would see the formal consequences of these realities in Le Violon d’Ingres, Hotel of the Heart, and subsequent volumes.

Stone Dragon Bridge: Poems of China 2006-2007

Richard Milazzo

With an Italian translation and preface by Brunella Antomarini.

First edition hardcover: 2007.

116 pages, 500 numbered copies, with an original cover by Enzo Cucchi,

a sepia-toned photograph of the author on the Lijiang River, China, January 2007, by Joy L. Glass

on the frontispiece, and a cyan-toned photograph by the author, 6.75 x 5 in.,

printed, sewn and bound in Savignano sul Panaro, Modena, Italy.

Published by Emilio Mazzoli Editore, Modena, Italy, 2007.

Richard Milazzo’s Stone Dragon Bridge: Poems of China 2006-2007 documents the author’s first trip to China. In Beijing, he seeks out the remaining hutongs (alleyways) and siheyuan (courtyard houses) of old Peking. In Shanghai, he gazes down the Bund at night from his hotel room and tries to imagine what this famous boulevard was like before it was architecturally redimensionalized in the name of progress. He bemoans the loss of the Old Pudong district, a backwater area located on the east bank of the Huangpu River (bisecting Shanghai and intersecting the Yangzi River downstream) facing the Bund, once the city’s poorest quarter, filled with slums and brothels, now razed to the ground, assigned the status of Special Economic Zone, and become one of the largest development sites in the world – “a new kind of corporate slum filled with nothing but glass and steel skyscrapers.” He visits Xi’an, in Shaanxi province, which was, in the 9th century, the largest and richest city in the world, and the starting point of the Silk Road; and Guilin, in Guangxi province, and journeys along the Lijiang River in Southwest China, known for its karst peaks, which have inspired painters and poets for centuries.

The Italian philosopher Brunella Antomarini writes of the poet’s work: “he describes the memories of a journey in which the time of a lived experience is confused with historical time, the pleasure of a gaze embraces centuries of dramatic events, and the corporeal pace is at one with the pace of writing: ‘Walking became a style of writing, /... / leaving nothing but the sudden caesura / or slow chasm, indeed, / the measured enjambment of mortality.’ From verse to verse, from one language to the other, the vision of a internalized political condition unfolds, through a mediated perception, for the sake of an authentically felt poetry, seemingly exhaled from earth itself and making its terrible moral weight bearable to us.”

An Earring Depending from the Moon:

Poems 2006

Richard Milazzo

First edition paperback: May 2008.

Designed by Richard Milazzo.

80 pages, gatefold covers reproducing in color drawings by Lawrence Carroll,

with a black and white photograph of the author by Joy L. Glass, Venice, November 2006,

on the frontispiece, 9.25 x 6.5 in., printed, sewn and bound in Turin, Italy.

ISBN-13: 978-0-9793507-1-9. ISBN-10: 0-9793507-1-9.

Published by Sotoportego Editore, Dorsoduro and Giudecca,

Venice, Italy: 2009.

In this, the peripatetic author’s most recent book of poetry, An Earring Depending from the Moon: Poems 2006, Richard Milazzo writes more darkly than usual about a world that seems to be dangling over a precipice. Whether he is in New York, North Florida, London, Venice or Vienna, the storm clouds of the human condition in today’s society overtake his vision.

In the North Florida poems, desire and oblivion are objectified through the landscape. The fragrant world of honeysuckle and jasmine, and W.C. Williams’ little red wheelbarrow, upon which “so much depend[ed],” are diverted by the darker realities of divorce, missing children and aging. ‘Ring Around the Rosey’ and ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ are reprised in a more ironic context that takes on Biblical overtones, as Revelations, in this author’s view, no longer gainsays reality. Evocations of Shakespeare’s sonnets and Coleridge’s “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” are brought to bear upon the specter of human existence in its most despicable and primal manifestations. “If it becomes given that story is not incompatible with the lyrical intensity of the sonnet or any other so-called non-narrative form, then wanting, as I do, with each poem, to tell a story, I should not have to sacrifice the orgasmic (or Dionysiac) intensity of the lyric.” We are, here, the poet argues, in “the land of last things, which we must always take as a possibility and reconvene as possibilities.”

At the center of this book of poems, An Earring Depending from the Moon, is the ultimately inapprehensible world of Venice in winter, a dark and elusive place that hardly exists beyond the romance of stone and the imagination running wild. “All stories interest me. Poems should have beginnings, middles and ends. At least mine ought to if they are not to fall back into the Modernist or ‘forward’ into the Postmodernist precipice."

Circus in the Fog: Poems 2005-2006

Richard Milazzo

First edition paperback: May 2009.

Designed by Richard Milazzo.

88 pages, with a black and white photograph of the author by Joy L. Glass,

Piazza Ruggero Settimo, Palermo, Sicily (Italy), on the frontispiece,

7.5 x 4.5 in., printed, sewn and bound in Turin, Italy.

ISBN-13: 978-0-9793507-26. ISBN-10: 0-9793507-2-7.

Dorsoduro, Venice, Italy: Sotoportego Editore, 2009.

In Circus in the Fog: Poems 2005-2006, a book that might just as well have been subtitled, “Poems of Sicily,” the author, Richard Milazzo, who has written often and eloquently of Palermo in the past, his father’s birthplace, writes for the first time about the isle of Sicily, its people, its cultural heritage and his family. Figures such as Antonello da Messina in Cefalu, the grandparents on the author’s mother’s side of the family in the slum town of old Favara in the southern province of Agrigento, Lazarus, Artaud, Anna Ahkmatova, Rosario Gagliardi of Ragusa Ibla, all figure somehow into the mix. The ‘circus in the fog’ – a kind of half-breed, gypsy ontology – is everywhere full of the sea, blood, stone, hyacinth, snow, “broken kisses” and the black branch in winter. Evocative of Lawrence Durrell’s “Sicilian Carousel” and Picasso’s “Family of Saltimbanques,” it is written in a verse style that is in places leud but always graceful and full of “Carthaginian grace.” And lurking in the shadows of this perpetual winter of our discontent, we find fragments of New York City – a city that “means next to nothing to me” – Basel, London, Paris, St. Louis (Missouri) and Santa Monica (California). “The world is a circus lost in a fog.”

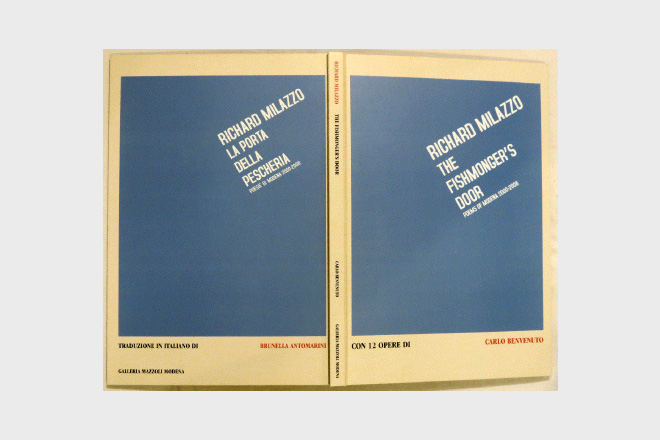

The Fishmonger’s Door:

Poems of Modena 2000-2008

Richard Milazzo

With an Italian translation by Brunella Antomarini, photographs by Carlo Benvenuto, and a preface by the author.

First edition hardcover: July 2009.

112 pages, 300 numbered copies, with a black and white photograph of the author,

Hotel Canalgrande, Modena, Italy, June 2005, by Joy L. Glass on the frontispiece,

10 color reproductions and a black and white photograph of the publisher by the artist,

16 x 11 in., printed, sewn and bound in Modena, Italy.

Modena, Italy: Galleria Mazzoli, 2009.

Eastern Shadows: Poems of Romania, 2008-2009

Richard Milazzo

With a Romanian translation by Adrian Sângeorzan.

First edition paperback: January 2010.

160 pages, with a black and white photograph of the author,

Luxembourg Gardens, Paris, July 2007, by Joy L. Glass on the frontispieces,

and color photographic illustrations on the cover by the author,

8 x 5.75 in., printed, sewn and bound in Romania.

ISBN: 978-606-8031-38-5.

Published by Scrisul Romanesc, Craiova, Romania, 2010.

Eastern Shadows: Poems of Romania 2008-2009 by Richard Milazzo comprises the poems the author wrote mostly while in Budapest and traveling across Romania in the winter of 2009. The titles of the poems give us some idea of the book’s subject matter: “Budapest Dream,” “Tomb of Gül Baba,” “Gellért Hill: Song of the Four Elements,” “Szabadság Bridge,” “Everywhere in Buda,” “The Trams at Ter Gellért,” “Bucharest,” “Stavropoleos,” “The Fences of Romania,” “What is Held in Shadows,” “Liar’s Bridge,” “Sibiu,” “Sighisoara,” “Cluj,” “Sighisoara II: The Scholars’ Stair,” “Desesti,” “Memory of the Pain,” “Merry Cemetery at Sãpânta, Rasca,” “Moldavita,” “Sucevita: The Ladder of Virtues,” “Arbore,” “Voronet,” “Humor,” “The Black Church of Brasov.” The tall wooden churches and painted monasteries of Northern Romania – the Maramures and Moldavia – visited while traveling along the derelict, if not wholly abandoned, and snow-covered infrastructure of the country, become an effective way for the author to establish a lyrical infrastructure in the poems that reflects allegorically a culture of wood, a poignant spiritual interiority, and irrepressible erotic underpinnings, qualities and attributes that would ultimately stand their ground against and prevail over what once was, in the not so distant past, and metaphoricaly speaking, a tyranny of metal, i.e., a Communist military dictatorship that ruled with iron fists and the proverbial iron boot, and that is only now finally thawing. The intangible, even abstract, but sensuous lyricism of Easter Shadows is firmly rooted in the complex political and social reality of this forgotten country in eastern Europe, the author often turning to the poor, the louche, and outré gypsy culture to reaffirm the threshold values inherent in the struggle to become human again.

Small China Moon: Poems 2002

Richard Milazzo

With an Italian translation and an afterward by Peter Carravetta.

First edition paperback: November 2010.

176 pages, with a black and white photograph of the author, Hotel Due Torre,

Rome, Italy, January 2003, by Joy L. Glass on the frontispiece,

and a color illustration by Ross Bleckner,

6.5 x 4.75 in., printed, sewn and bound in Italy.

ISBN: 978-88-456-1196-4.

Published by Campanotto Editore, Pasian di Prato (Udine), Italy, 2010.

Each poem in Richard Milazzo’s Small China Moon: Poems 2002 contains the word ‘China,’ ‘Chinese’ or other related word, this in lieu of the trip to that country which did not take place in the summer of 2002. The author would finally go to China five years later, in 2007, and write while he was there, Stone Dragon Bridge: Poems 2006-2007. Still odder, a preponderance of the poems in Small China Moon were written in New York City, with the exception of a handful written in Prague and the American Southwest. About this book the Italian scholar, poet, and translator Peter Carravetta writes: “It should be obvious that, at the formal level, the work in Small China Moon, is making a case for a poetry no longer of the flash, the spark, the overwhelming but mute image, but rather a telling of the vicissitudes of the living self, asserting itself stoically in the thrownness of being in this our irremediably alienated world, a plenum with no beginning and no end, just a passing-through.”

Here, the lyric and the narrative impulse meet on a level playing field, where the formal concerns of the poem do not preside exclusively over the ever-elusive ontological realities fueling it. Rather than becoming the “army of language” (John Cage), syntax loses itself in the pursuit of an object of desire it would overwhelm and devour but to which it cannot even draw near, much less consume – whether this be a woman, the Other, or a whole country. “I am still not convinced / the sun will dance with us tomorrow, / or the moon bring both sides / of the night together, to bed, tonight.”

Keats Dying in Your Arms:

Poems 2007-2008

Richard Milazzo

First edition hardback: November 2010.

Designed by Richard Milazzo.

120 pages, with a black and white photograph of the author,

Serjilla (City of the Dead), Syria,June 13, 2008, by Joy L. Glass on the frontispiece,

6.5 x 4.75 in., 400 copies, plus 100 with slipcase, printed, sewn and bound in Brussels, Beligum.

ISBN: 1-893207-32-3.

Published by Éditions Passage St.-Hubert, Brussels, Belgium, 2010.

Keats Dying in Your Arms: Poems 2007-2008 by Richard Milazzo was written in Jacksonville (Florida), Havana (Cuba), Palermo (Sicily), Santa Monica (CA), Basel, Venice, but mostly in Kracow and Warsaw, Poland. While it is, in part, a sorrowful book, indeed, sometimes mournful in tone, where it considers the events of World War II in Poland, there is also what could be described as a redemptive erotic undertone that finds its way into the writing as the poet travels from place to place.

Keats Dying in Your Arms is perhaps one of the author’s most personal and revealing books, trying as it does to reciprocate the cruelties of life and the cycle of mortality with caresses hardly rendered and hardly felt, and that have absolutely no chance of surviving what is often the horror of the human condition. But the poems are unrelenting, nonetheless, in the way they seek out, and sometimes find, absolution in the smallest details that can often go by unnoticed or in abstract lyrical gestures that would embrace the world at its most sublime and even at its lowest depths. In the poem “Vistula,” the poet writes: “On the banks of my hips and thighs / you have lain, and lied / to me and to yourself / about the beauty of the world, // even as you were simply resting / from your exploits, from the truth / of your brutality, and even as I felt / the limbs of your trees, // like black tongues, / burrowing into the gray void of the sky, / and dissolving with the wind / like black smoke.” And in “The Ash Pond,” he writes: “There are ponds of ash / from which no phoenix can rise – / and should it rise ever despite the flames / and the black smoke, // it shall not burgeon on the wings / of histories buried nor blossom / on wings of forgiveness extended / nor fall back to earth in tears of rain. // Its wings shall beat to rhythms / unheard of before in the heart and plummet / to depths of sorrow and despair unencompassable / by cloud and sky and soul’s extent.”

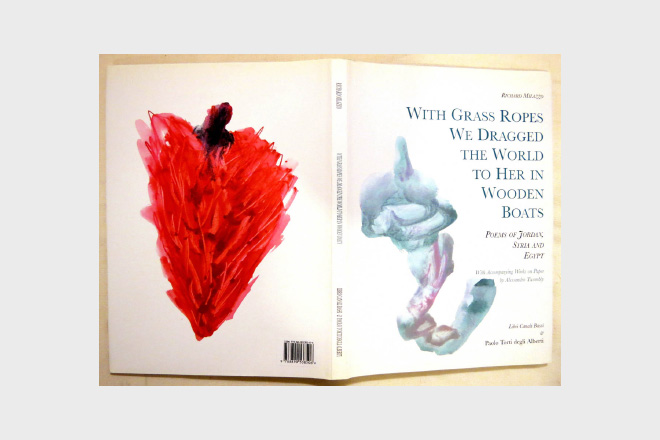

With Grass Ropes We Dragged the World to Her in Wooden Boats:

Poems of Jordan, Syria, and Egypt, 2008

Richard Milazzo

With works on paper by Alessandro Twombly and a foreword by the author.

First edition hardback: November 2010.

Designed by Richard Milazzo.

112 pages, with a 4-colour gatefold jacket, a black and white photograph of the author and artist,

Caffé Rosati, Piazza del Popolo, Rome, Italy, June 2, 2009, by Joy L. Glass

on the frontispiece, and 27 color reproductions, 12.75 x 9.5 in.,

500 copies, plus 25 special deluxe boxed edition with six prints by the artist,

printed, sewn and bound in Turin, Italy.

ISBN-13: 978-88-905385-0-6.

Published by Libri Canali Bassi / Paolo Torti degli Alberti,

Cumiana, Italy, 2010..

About Richard Milazzo’s With Grass Ropes We Dragged the World to Her in Wooden Boats: Poems of Jordan, Syria and Egypt (2008), the Romanian poet and novelist, Adrian Sângeorzan, writes: “In his search of history and language, this rare traveler-poet brings to perception a curious and vivid third eye. Wherever he goes, the light of its sensibility refines sounds, images and ideas, compresses myths and emphasizes mysterious lost cities, surreal landscapes, solitary deserts and dead seas, seemingly bringing back to life civilizations not yet dead.

“The poetry, fused to the works on paper of Alessandro Twombly, creates for the reader a perspective, a cinematography, of places and cultures linked by a silent desert, by the fragrance of eucalyptus and myrrh, and by an indestructible light inside the stones and fragility of time.

“More than merely contemplative witnesses, the poet and artist here become provocative warriors challenging the common and predictable perceptions of reality and legends. Where the artist is attracted not only by the depth but also by the surface of things, the poet sees the bones of the moon in the mountains of Jordan, even as he catches the essence of Syria by telling the simple story of a girl in a café. Both have the rare gift of revealing the Orient in its negligee, glistening in the sun, with the past and present mingled by the sand and the sea.

“The poet’s Orient in this book is a complex souk of feelings and smells, tombs and mosques, legendary gods and ordinary people lingering under a luminous sky filled with ivory, sphinxes, obelisks, swords, precious stones and the cheapest and most transcendent of dreams. From Petra to Wadi Rum, the poet walks on a rope of grass, and in magical wooden boats he crosses from Damascus to the Valley of the Kings, dragging the world from ruins and cruel reality to mystery and joy. It is a poetry so open that it allows itself to be transformed by the hidden beauty and truth of other people and places.”

A special deluxe-boxed set, in an edition of 25, has been produced to celebrate the publication of this book. It contains a signed and numbered copy of the book and six prints based on the works on paper reproduced in the volume.

Where Angels Arch Their Backs and Dogs Pass Through:

Poems of India and Nepal, 2010-2011

Richard Milazzo

With a Romanian translation by Razvan Hotaranu.

First edition paperback: July 2012.

160 pages, with a black and white photograph of the author, Old Fruit Market, Bombay, India, January 13, 2011,

by Joy L. Glass on the frontispieces, and color photographic illustrations on the cover by the author,

8 x 5.75 in., printed, sewn and bound in Romania.

ISBN: 978-606-8229-48-5.

Published by Scrisul Romanesc, Craiova, Romania, 2010..

Where Angels Arch Their Backs and Dogs Pass Through: Poems of India and Nepal 2010-2011 by Richard Milazzo was written mostly in India and Nepal and published in Romania with Scrisul Romanesc. There are also in this volume poems written in Paris, Milan, Florence, and Venice. The titles of the poems in Where Angels Arch Their Backs and Dogs Pass Through give us some idea of the book’s scope: “Arjuna,” “Chandni Chowk,” “Humayun’s Tomb,” “Qutab Minar,” “Hallucination in Kathmandu,” “Bhaktapur,” “Prayag Ghat,” “Varanesi,” “At the Cremation Ghat,” “Queen Elizabeth’s Suite,” “Khajuraho,” “The Palace of One Night,” “Agra Fort,” “In the Shadow of the Taj Mahal,” “The Palace of Wind,” “Dream of the Great Sundial,” “Kali,” “Jain Temples,” “Udaipur,” “Bombay.”

The poet brings his unique form of narrative lyricism to his travels through this vast and complex country. And he manages as always to find not only in the architectural monuments but in the history of these stones erotic predicates: “But what a night it was! / Moon’s first glimmer of her, / through a latticed stone screen, her skin, / sandstone polished to a white glow! // All precious stones / cast their designs upon her – / chiefly lapis lazuli and turquoise, / with a tremulous gold entablature! // And her cupolas - Islamic and Hindu, / smooth and ribbed, so delicate and graceful –, / it was as if her walls had become / swirls of pure deity!”

It is difficult to call this writer an American poet, given not only the content of his work but his aversion to all things academic and culturally predetermined. It should surprise no one that after publishing fifteen books of poetry in Italy, Serbia, Romania, and Japan, in the course of twenty years, he is still without an American publisher. Here is a global poet who has yet to publish a single book in his own country!

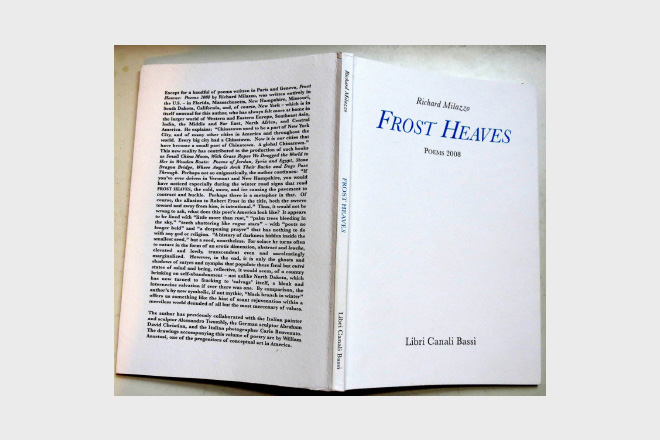

Frost Heaves: Poems 2008

Richard Milazzo

With drawings by William Anastasi and a foreword by the author.

First edition paperback: September 2013.

Designed by Richard Milazzo.

80 pages, with a 2-colour gatefold jacket, a black and white drawing of the author by William Anastasi,

New York City, October 15, 2008, on the frontispiece, and reproductions of 10 graphite drawings on paper,

8 x 5.5 in., printed, sewn and bound in Turin, Italy.

ISBN-13: 978-88-905385-3-7.

Published by Libri Canali Bassi, Cumiana, Italy, 2013..

Except for a handful of poems written in Paris and Geneva, Frost Heaves: Poems 2008 by Richard Milazzo, was written entirely in the U.S. – in Florida, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Missouri, South Dakota, California, and, of course, New York – which is in itself unusual for this author, who has always felt more at home in the larger world of Western and Eastern Europe, Southeast Asia, India, the Middle and Far East, North Africa, and Central America. He explains: “Chinatown used to be a part of New York City, and of many other cities in America and throughout the world. Every big city had a Chinatown. Now it is our cities that have become a small part of Chinatown. A global Chinatown.” This new reality has contributed to the production of such books as Small China Moon, With Grass Ropes We Dragged the World to Her in Wooden Boats: Poems of Jordan, Syria and Egypt, Stone Dragon Bridge, Where Angels Arch Their Backs and Dogs Pass Through. Perhaps not so enigmatically, the author continues: “If you’ve ever driven in Vermont and New Hampshire, you would have noticed especially during the winter road signs that read FROST HEAVES, the cold, snow, and ice causing the pavement to contract and buckle. Perhaps there is a metaphor in that. Of course, the allusion to Robert Frost in the title, both the swerve toward and away from him, is intentional.”

Thus, it would not be wrong to ask, what does this poet’s America look like? It appears to be lined with “little more than rust,” “palm trees bleeding in the sky,” “teeth shattering like rogue stars” – with “poets no longer held” and “a deepening prayer” that has nothing to do with any god or religion. “A history of darkness hidden inside the smallest seed,” but a seed, nonetheless. For solace he turns often to nature in the form of an erotic dimension, abstract and louche, elevated and lowly, transcendent even and unrelentingly marginalized. However, in the end, it is only the ghosts and shadows of satyrs and nymphs that populate these feral but outré states of mind and being, reflective, it would seem, of a country brinking on self-abandonment – not unlike North Dakota, which has now turned to fracking to ‘salvage’ itself, a bleak and internecine salvation if ever there was one. By comparison, the author’s by now symbolic, if not mythic, “black branch in winter” offers us something like the hint of scant rejuvenation within a merciless world denuded of all but the most mercenary of values.

The author has previously collaborated with the Italian painter and sculptor Alessandro Twombly, the German sculptor Abraham David Christian, and the Italian photographer Carlo Benvenuto. The drawings accompanying this volume of poetry are by William Anastasi, one of the progenitors of conceptual art in America.

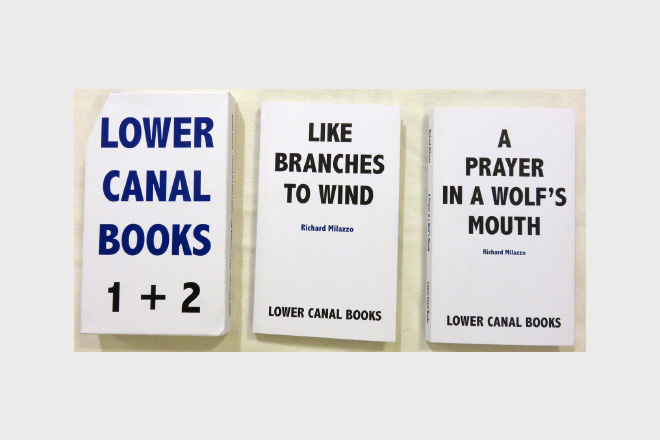

Like Branches to Wind: Poems 2004

and

A Prayer in a Wolf’s Mouth: Poems of South India, 2013-14

Richard Milazzo

Two-Volume Boxed Set:

First edition paperbacks: January 2015.

Designed by Richard Milazzo.

Volume 1: 88 pages, with a 2-colour gatefold jacket, a black and white photograph of the author,

Paris, June 2004, by Joy L. Glass on the frontispiece,

with reproductions of 32 watercolors by Charles Clough,

a preface by the author and a note by the artist.

Volume 2: 96 pages, with a 2-colour gatefold jacket, a black and white photograph of the author,

Hotel Metropole, Mysore, India, July 22, 2013, by Joy L. Glass on the frontispiece,

7.5 x 4.5 x .8 in., printed, sewn and bound in Turin, Italy.

ISBN-13: 978-88-905385-4-4. ISBN-13: 978-88-905385-5-1.

Published by Lower Canal Books, Cumiana, Italy, 2015.

In Like Branches to Wind: Poems 2004, Richard Milazzo writes: “The poems, my poetry in general, often rely on the physical elements and basic emotions (however we may paradoxically define such complex things) to tell their ‘stories’ – and there is the predilection itself in them to tell stories, which is, in my opinion, the most elemental of all human impulses, all enterprises. The pseudo sonnet form of three stanzas of four lines each – the minimum formal threshold of each poem – is nothing more than an excuse to reinstate the classical (or anti-postmodern) idea of a beginning, middle and ending for each story-telling poem […]

“But for all of their penchant to tell a story, they often strike an abstract note, reaching for something beyond the purely elemental. Having this abstract dimension of things in common with Charles Clough’s work in general, as well as the date in relation to this particular body of work (2004), the collaboration seemed like an ideal ‘marriage of reason and squalor’! In their combining narrative and lyrical, story-telling or representational and abstract components, they seemed to complement each other perfectly […]

“If Clough sees his method of working as ‘representational of style,’ in so far as his inclination is to reference other artist’s styles and styles of representation in these works on paper – a very postmodern methodology, if ever there was one –, thusly effecting a meta-style or what he identifies as an instance of pareidolia (the syndrome of seeing the familiar in the unfamiliar, as in seeing the face of God unexpectedly in the water stains of a bed sheet drying in the breeze), then I am similarly afflicted, in so far as I see the content, and indeed some of the images, if not the form per se, of my poems in his monochromatic and black and white works on paper included in this book. How does Clough put it…he sees in the poems and his images ‘an atmosphere replete with flashes of pareidoliac wraiths cavorting!’ But don’t we all see ourselves in a great work of art? And the greater the work, the more welcoming.

“And there are other related overlaps. Clough speaks of the classical Chinese style of working, the ink and brush medium. To utilize paper, ink or watercolor, and brushes is to incorporate into one’s practice, at least, theoretically, wood (fibers, bamboo pulp, for the paper; burned pine wood for the ink), animals (or, at least, animal hair for the brushes – soft goat hair and hard wolf hair), water, soot, stones (these, along with camphor and glue, to help make the ink), other mineral and vegetable elements (for the pigments). Besides the direct or indirect references in the poems to these painterly ingredients, the title itself of the book, Like Branches to Wind, is evocative of the gesture of a Chinese paint or watercolor brush grazing, interacting, with the surface of the paper. Not to mention the obvious, that what poetry (writing or calligraphy) and painting or drawing have in common is precisely the brush, at least in the classical ages of Chinese and Japanese art, as well as in many other cultures […]

“What they have in common is the ‘brushing’ gesture in its most open or loosest form (the Chinese identify this technique as i-pin). While the poems are strict or disciplined in their utilization of certain stylistic conventions, or the contours thereof – in the case of the sonnet form or the four-line stanza in general, in their giving of specific dates and places of composition of each poem –, they remain loose or open, indeed, downright louche, in their willingness to engage the world and its contents indiscriminately and without reservation. The poetry proceeds from poem to poem, in a linear fashion, as it were, not by themes, even though certain themes, certain tropes, might emerge along the way. They are organized chronologically, and place is determined by wherever I am at the time, whatever country I find myself in. There is no such thing as a poem that is inappropriate relative to any given book. Nor is there any concern about presenting the reader with anything other than the momentary life of a poem. Narrating that lyrical moment is all that matters to me, much in the same way that the most effective way of handling the brushstroke is quintessential to how Clough renders an image at any given moment, no matter how light or heavy to the touch, no matter how remote or proximate, no matter how literal or abstract.”

In this, Richard Milazzo’s nineteenth book of poetry, A Prayer in a Wolf’s Mouth: Poems of South India, 2013-2014, he travels halfway around the world to South India, to the states of Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Karnataka. In his first book on India, Where Angels Arch Their Backs and Dogs Pass Through: Poems 2010-2011, published with Scrisul Românesc in Romania, in 2012, he had traveled through several of the northern and central states of the Indian subcontinent. But, as in the previous book, he does not do so without visiting other places during the course of the book’s life – in the case of A Prayer in a Wolf’s Mouth, Paris, Vienna, Amsterdam; Modena, Florence, Venice; and, in the States, Jacksonville, St. Louis, Philadelphia, and Santa Monica. And, of course, interspersed are poems written where he lives and works, New York City.

Before traveling south, the poet lingers in New Delhi for a week, where he laments, in the voice of a young girl: “Here, I shall meet no one who matters to me, / and I, too, shall fade from memory. // Not the stone nor the low-lying reeds / shall note my passing – / not even the lowly lorry driver, / once so handsome and so youthful!” During his travels south, the poetry takes for its subjects love, rape, hunger, sewage, unbridled eroticism, martyrdom, the monsoons, democracy, time, fate, death, colonialism, and the ceremonies and rituals that still go to the heart of India, even to this day. “All of it passing softly in an eye,” he says, “blinded by truth.” Many of these matters are personified through the figures of the River Yamuna, the Bay of Bengal, the snake stones of Madras, Vishnu’s consorts, and even Gandhi’s loincloth! Nothing is sacred and yet every detail is scrutinized and cherished. “We are,” he concludes, “mannequins manipulated by the wind, / gods and goddesses bursting / into the cold flames of a dying mirror, / a prayer in a wolf’s mouth.”

In Paris, his attention turns to Catherine Deneuve, God, Michelangelo’s Drunken Bacchus, de Saussure, and an analysis of the café mechanism of world-watching; in Vienna, the inspirations become Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze, St. Francis of Assisi, and Frank, the new Pope; in Amsterdam, Van Gogh and Artaud taunt our perceptions. In Modena, the bicycle riders and the tram wires overhead precipitate, like Proust’s madeleine, a meditation on time; in Florence, Giotto, Brunelleschi, Michelangelo, Nicodemus, Donatello are coaxed into an architectural erotics. Post-humanism and the ontological nonfinite; Orcagna, Cellini, Giambologna, and an allegory of corporate violence; Cimabue and the Arno flood of 1966, all seem to coalesce into a dark metaphysical world of Florentine conspiracy and tragedy. In his uniquely “stray world” of Venice, always on the verge of snow, we stumble across his imaginary friends, Tintoretto, and the Russian writers, Vladimir Nabokov and Joseph Brodsky, and in reality, the contemporary artist, Lawrence Carroll, in whose besmirched realms of whiteness Ryman and Morandi are implicated. No matter to what tropical or wintry corner he turns, our poet discloses that “A weightless but ponderous creature we have become / alighting barely upon the laurel branch, / without the semblance, the airy displacement, / of a wingèd species lost to rhyme and meter!”

Amid all of these Indian and European ruminations, we sporadically find ourselves back in the States, in the backwaters of a dwindling world, as it were. In Jacksonville, Florida, he asks: “And what is the fragrance of the river to me, / this curtain pulsing, / the Spanish moss weeping in the wind – what are they to me / beyond this moment beating?” Using again the St. Johns River, rather than the sacred Ganges, he confutes the benighted Language-writing school of his generation, committed seemingly to difficulty for difficulty’s sake: “What part of this poem should be more difficult / than the fire of the heart / consuming the grasshopper and the owl, / the frog and the egret?” And with this in mind, like a latter-day fauvist or Kafkaesque metaphysical insect, he would “relanguage the world with songs of pure intent, / this is where I linger among the shadows and wait / for the parts hidden inside your heart to return to me!” Although we speak of the poor suffering and dying in the streets of Bombay and Calcutta, we conveniently overlook the ‘neighbors’ who die unnoticed in the apartments next to ours in New York City. Amid reflections of youth and old age, there abides the realization that “the present is something we can never fully realize.” “We are, after all, merely hysterical residues of flesh darkly spent!”

Road Narrows:

Poems of Tunisia, 2013

Richard Milazzo

With a Romanian translation by Alexandru Oprescu.

First edition paperback: December 2014.

112 pages, with a black and white photograph of the author, Tunis, Tunisia, June 12, 2013,

by Joy L. Glass on the frontispieces, and color photographic illustrations on the cover by the author,

8 x 5.75 in., printed, sewn and bound in Romania.

ISBN: 978-606-674-058-6.

Publsihed by Scrisul Romanesc, Craiova, Romania, 2014.

Poems written in Tunisia which collapse erotic incident, archeological sites, and history into each other. While some of the poems were also written during the author’s travels in the French midi, all are infused with an inner as well as an outer light that must also negotiate the darkness of the soul.

“I assigned the book the title, Road Narrows, because I felt that life generally narrows to a point – that is, if we are lucky, if we live long enough to even experience it in that way –, which geometrical figure (the ‘point’) we all know is dimensionless. It narrows, if not vision-wise then surely time-wise. Temporality is unforgiving, no matter the forms into which science may twist and turn it, no matter our ‘travels,’ whether literal or figurative, through the world (of experience), no matter all the ads in the airports to the contrary. Calling the affects the passage of time has on us ‘temporality’ will not mitigate, will not deflect, the encroaching reality. Distancing ourselves from these realities, which we do so well as Americans, lauding the value and values of youth and the youth-culture, will not change this. We cannot botox away, we cannot surgically wiggle our way out of, this condition.

“The title Road Narrows actually came to me from the road signs I saw approaching the airport in New York City on my way to Nice. But I have been aware of the sign for a very long time, especially in the New England states. (Just as I was aware of the road sign Frost Heaves, which became the title of another book of poems.) It just didn’t resonate with me metaphysically, and certainly not existentially, until it finally hit me, at first intuitively and then consciously. And then, coincidentally, in Kerkouane (in Tunisia) my guide explained to me that the medina roads – indeed, all roads – tend to narrow geologically over time, imperceptibly, millimeters at a time over millennia, no matter how robust the stones. Apart from the general wear and tear, the road pushes upwards toward the center, which trajectory might be interpreted as a form of transcendence (if we are desperate for such redemption), or also as a last gasp.

“Then, in Carthage, where I fell in love with Punic civilization, the title Road Narrows, took on additional meaning, perhaps precisely because there is so little of this civilization that has survived. Even the brilliant light of Tunisia, which was instrumental in transforming the art of Paul Klee, and the comparably beautiful light of the midi, which was transformative for the work of the great French artists of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, should not blind us to the comparable darker realities invariably accompanying any great effulgence.

“My thanks again to Carmen Firan for getting behind this publication, which is, in fact, my third book published with Scrisul Românesc. Eastern Shadows was published in 2010, which contained the poems written in Romania, and Where Angels Arch Their Backs and Dogs Pass Through in 2012, containing the poems I wrote during my first trip to India. I must also thank Florea Firan, the editor and publisher of Scrisul Românesc, for his persistence, understanding and tolerance. It is more than a little strange to publish two books – one written in India, the other in Tunisia – in Romania, and to have written in addition some sixteen other books of poetry, published mostly in Italy, and in Japan, Serbia, and Belgium, but to have published none in the United States. Perhaps this is not so strange, since the only thing, or two things, I have loved about the U.S. is the endless influx of immigrants who make this country a little less Protestant, white, and provincial, and the vast, uncontainable expanse, the feral diversity, of its geography. Publication in Romania and elsewhere, and given the books of poems I have written (some published, many still unpublished) in Southeast Asia, Russia, North Africa, China, Central America, Mexico, South America, Eastern and Western Europe, has turned me into a kind of global emigrant, for which I am most grateful.”

A Tattoo in Morocco:

Poems 2007

by Richard Milazzo

With drawings by Mimmo Paladino

and an Italian translation by by Brunella Antomarini.

First edition hardback: September 2015.

Designed by Richard Milazzo.

186 pages, with color covers by Mimmo Paladino, a black and white photograph of the author,

Erg Chubby Dunes, Sahara Desert, Morocco, June 25, 2007, by Joy L. Glass on the frontispiece,

and 12 drawings, 1 portrait, and a note by Mimmo Paladino.

8 x 6 x .75 in., 500 copies, printed, sewn and bound in Savignano sul Panaro, Italy.

ISBN-10: 1-893207-36-6.

ISBN-12: 978-88-905385-0-6.

Published by Edizioni Galleria Mazzoli, Modena, Italy, 2015.

A Tattoo in Morocco: Poems 2007 was not only written mostly in Paris, Morocco, Basel, and California, it was written about these places. The author’s ongoing unrequited love affair with Paris and periodical visits to Basel are strangely mitigated by sustained meditations on the Holocaust and the art of poetry. An ontological sadness permeates the overall tone of the book.

Along the way, he discourses with such writers and artists as Primo Levi, Edvard Munch, Paul Klee, Gore Vidal, Paul Muldoon, and François Villon. At the heart of the book are the Moroccan poems, which, as is the author’s custom, infuse the places he visits in this country with a form of eroticism that is detached, if not impersonal, and yet intense, politically discursive and yet lyrical, intimately abstract and disturbingly familial.

For the author, tattoos are not unlike poems, often marrying image and text together, sometimes in shocking and at other times in enigmatic ways, but always reminding us the way simple numbers were once inked into flesh to proudly and perversely document one of the darkest periods in human history, not unrelated to our ongoing inhumanity.

Storyville: Poems 2010

by Richard Milazzo.

First edition paperback: January 2017.

Designed by Richard Milazzo.

112 pages, with a gatefold color cover reproducing a painting by George Hildrew,

48 original drawings created for the book by George Hildrew,

a black and white photograph of the artist’s studio, Brooklyn, New York, 2016, on the frontispiece,

and 2 original drawings of the artist and of the author by the artist.

9.25 x 6.5 in., printed, sewn and bound in Turin, Italy.

ISBN: 1-893207-37-4.

ISBN: 978-1-893207-37-0.

Published by Tsukuda Island Press, Hayama and Tokyo, Japan, 2017.

About Storyville: Poems 2010, Richard Milazzo writes: “Apart from our usual visit to North Florida in the Fall, it was the BP oil spill of April 2010 that brought us to the Gulf of Mexico that summer. This event seemed categorically reckless to us, ontologically and grossly (globally) negligent in a most criminal way, if not downright apocalyptic in its immediate and long-term ramifications. The Gulf had always been a small (personal) but significant part of our lives and we, like so many others, were in a state of disbelief about what had happened. Like the Biblical St. Thomas channeled by Leonard Cohen, we wanted to put an evidential finger into the wound, knowing, however, that the proverbial crack in this world – more like a deep-structural topological stain – would not yield any light but rather the never-ending overwhelming darkness of corporate greed and deleterious self-interest.”

The author stopped in Mobile and Bayou Le Batre in Alabama; Jackson, Natchez and Biloxi, Mississippi; Baton Rouge and New Orleans, tracking the levees and excavating the cultural residues of Storyville, the legendary red light district of N.O. Along the way, he brings us face to face with Faulkner, Goya, De Kooning, Degas. There are extended stays in Niagara Falls, Paris, Modena, Rome, where we encounter Pasolini, the Venus of Willendorf, Rilke’s Balzac, Willard Van Orman Quine, David Hockney, each figure yielding a story of some kind, both of a historical and figurative nature. But it is not so much the stories that shape the poems, which have been described unflatteringly as “history poems” and “template poetry,” not that he has found anything objectionable with this approach; rather, it is the underlying reality, often ungraspable, that configures the syntax of the poems and generates a level of abstraction wholly unexpected. What is lyrical in this poetry is in no way antithetical to the narrative extension of the poems, which are everywhere unabashedly desirous to communicate with the reader and in no way infatuated with the intellectualism of writing that is difficult for difficulty’s sake. Whatever is Brechtian or distanced or self-distancing in these poems is dedicated to the lowest reaches of human desire and humanity, no matter the motive or the result.

About the artist George Hildrew, whose works parallel the poems in this volume in a non-didactic manner, the author explains: “it is the quirky aspect of his work that has always intrigued me. I have known George since the late 1980s. His paintings are psychologically de-centered and de-centering, abstract yet lyrical, erotic yet detached, deflecting narrative pigeonholing but discursive in the most minute and unsuspected ways. And he is simply not afraid to tell stories, in and out of school. Stories about our inhumanity, as well as our humanity. His is an incisive intellect and sensibility, utterly deracinated from any conventional sense of good taste, not to say down and dirty, that is, if only we could grasp the subject of his eternally quixotic visual ‘sentences’ and the object of their hidden desires. Japanese anime and manga have nothing on Hildrew’s figures swirling and writhing in his dark comic book world or perversely odalisquing on a couch in Freud’s Vienna,” now reduced absurdly to nothing more than a boudoir inside a fortune cookie.

“I love it that drawing is the primary mover of Hildrew’s aesthetic, not that his esoteric use of color does not complement his strange vision of the world. The 50 original drawings – black ink on 12 x 9 in. Strathmore Bristol paper – created for this book were executed in five months, from May to August 2015, and are reproduced here actual size. If they are illustrative in any way, they are also illuminating, but, in the end, unruly and unyielding, no matter how much they want us to read into them. Their parallel life with the poems in no way cripples them as autonomous creatures in a threshold world. He has the ability to plumb the most obscure and simultaneously universal corners of the psyche, always however letting his psychological adventures determine or frame the formal parameters of his pictures. And his works always exploit the absurd and humor in behalf of no higher moral or ethical authority other than that of his extremely reserved but eccentric soul.”

Together, the poems and drawings in Storyville tell the larger story of contemporary culture having entered and seemingly not returned from the worm hole of a robotic technological cartoon world of one-dimensional values, neither really condemning nor validating it. At some level, it is as if the author and artist were walking down the same street, but going in opposite directions, and then crashing into each other like two wired techno-zombies (such creatures are ubiquitous today) reading their so-called ‘Smart’ phones, although in reality there is probably not (there actually isn’t) one Smart phone between them! Or it is like they are taking a selfie together, but the image turns out quite preposterously sorrowful and forlorn.

Ghost Stations: Poems 2015-2016

by Richard Milazzo.

First edition paperback: January 2017.

Designed by Richard Milazzo.

104 pages, with a gatefold 2-color cover reproducing in black and white

a rephotographed image of Oranienburgerstrasse train station, Berlin, Germany,

a black and white photograph of the author on the frontispiece by Joy L. Glass,

Berlin, Germany, April 14, 2015,

a portfolio of 36 black and white photographs and a text by Fausto Ferri,

and an introduction by the author.

9.25 x 6.5 in., printed, sewn and bound in Turin, Italy.

ISBN: 1-893207-38-2.

ISBN: 978-1-893207-38-7.

Published by Tsukuda Island Press, Hayama and Tokyo, Japan, 2017.

In the introduction to Ghost Stations: Poems 2015-2016, the author, Richard Milazzo, writes: “What else did we, did I, expect from a culture savagely feeding upon itself like cannibals? It is only natural this spectacle would lead to the world, ‘the romance[,] of the unbearable and inconceivable’. So what is our, my, saving grace? A Babylonian world in which we must learn that “love [comes] in inimitable, irreversible forms.”

About the portfolio of black and white photographs by Fausto Ferri, executed in 1974, and accompanying the poems in Ghost Stations, the author says: “When I look at the ruins of Ferri’s city, Castelfranco Emilia, not just the old buildings becoming older with time, but the architectural havoc and horror of urban development in the 1970s to the present, documented by him in the frankest, most factual, yet most poetic way, it becomes abundantly clear why we continue to spiral not just downwards but, as a species, wildly, in an all-encompassing, self-delusional, self-destructive manner.

“Which is to say, the ‘ghost stations’ of Berlin were not and are not the only ones in existence. In Berlin, there were literally four: Potsdamer Platz, Brandenburger Tor, Friedrichstrasse, Oranienburger-strasse (the latter illustrated on the front and back covers here), train stations in East Berlin that were closed to West Berliners during the period of the Berlin Wall, from 1961 to 1989. The trains would pass from West through East to West Berlin without stopping at these four stations in East Berlin, and it was these highly surveilled (sic) but abandoned stations that became known as ‘ghost stations’. In the United States, such ‘stations’ exist everywhere, in the form of thousands of city centers and downtown areas that were abandoned during the ‘White Flight’ of the 1970s (Whites fleeing the presence of Blacks), and thousands of other smaller urban areas that have all become essentially ghost towns (mostly due to the ubiquitous presence of the automobile and the loss of manufacturing jobs to corporate out-sourcing). What happened to Castelfranco Emilia happened to many urban areas around the world, especially in Third World countries, which were and continue to be exploited by urban developers, not only destroying city life but also the environment.

“But there are other kinds of related ghostly spectacles, often unsuspected or imperceptible – Bachelard-like, ghostly stations. It could be said they describe a phenomenology of “ghost corners,” which are not so overtly ideological in nature. These ‘corners’ include memories of a ‘ghostly lover’ (in Fausto’s case), or, in mine, the memory of an old reading room annihilated years ago at my college. In them, we can also find “little bastard dog[s]” (among them Fausto and me) sniffing at their more sensuous configurations; spectacles of helplessness and sorrow no matter where we turn (or wag our tails); a mournful ‘universe of walled-up windows’. ‘It was the time’, let’s face it, in Castelfranco Emilia and elsewhere, in the 1970s, ‘of sad butchers with blood-stained white aprons / staring off into the distance’.

“More generically, but not less humanely, there are the ghosts of those on Flight 93 who went down in a field in Western Pennsylvania, victims transformed into heroes by their collective actions on 9/11. And there are the ‘ghost iron and steel mills’ of Pittsburgh that no longer exist except as reminders of our ever-eroding self-sufficiency as a nation.

“Not just in ‘picturesque’ places like Dachau, but in picturesque places like Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, that is, in very unimaginably serene ghostly corners of the world, transpire unspeakable crimes against humanity. For it was in the Mount Washington Hotel in the White Mountains of this backwoods state, in July 1944, that the global take-over of nation-states by banks and corporations masking as nation-states was hatched as an idea and took place. It was at the Bretton Woods Conference that the IMF (The International Monetary Fund) was established.

“For me, personally, beyond the inhumane sweep of history, which is never more than a chain of pearls pieced together randomly, and often without regard to facts or to actual circumstances, there perdures still, against the odds, against time itself, the ghostly corners of places like Castelfranco Emilia, which Ferri has documented so affectionately and profoundly for us in his black and white photographs, underscoring the helplessness of these corners, these places, lost to the grander but far less authentic horizons and horizon-lines of history.

“About vision, about the things lost to history, about sorrow, there are Ferri’s own precious and beautiful words about the function of his photographs: ‘They are the candle inadvertently shedding light on a collective memory. I only hope these places and little stories might find their rightful place once more, latching onto each other to recreate that ‘grand tour’ of those little streets and courtyards within the context of their everyday life in those ordinary days of 1974’.”

One Thing at a Time: Poems of Japan, 2016

by Richard Milazzo.

First edition paperback: April 2017.

Designed by Richard Milazzo.

96 pages, with a gatefold color cover reproducing a photograph by the author,

30 original drawings created for the book by Abraham David Christian,

a black and white photograph of the author on the frontispiece by Joy L. Glass,

Basho-an, Kyoto, Japan, March 7, 2016,

and an introduction by the author.

9.25 x 6.5 in., printed, sewn and bound in Turin, Italy.

ISBN: 1-893207-37-4.

ISBN: 978-1-893207-37-0.

Published by Galerie Albrecht, Berlin, Germany, 2017.

OUT OF PRINT

On the occasion of publishing the book, One Thing at a Time: Poems of Japan, 2016, by Richard Milazzo, Galerie Albrecht presented the exhibition: One Thing at a Time: Drawings and Sculptures by Abraham David Christian, curated by the author. Besides the sculptures, the exhibition included the suite of 30 drawings (三十 [san jû]) Abraham David Christian made in Japan to “illustrate” the book.

In the Preface, the author writes: “Most of the poems (excepting two) in One Thing at a Time were written during a recent trip to Japan, in February and March of 2016. In the poems about Hiroshima, I felt sure indirection was the only possible approach. The hope is that the sincerity of my intentions will carry me and that no part of my life-long-shock will be misconstrued. As for the rest, we can clearly see at work here, in these poems, history rooted in the most visceral of ontological predications, where it is not simply symptomatic of an erotics of retrospection. When this author gazes up at the burgeoning fruition of the plum or cherry blossom tree, he sees only an overwhelming population, a fleeting consort and delicate conceit, of erotic thresholds. Clearly, he is dizzy with the pollen of existential spring, even as the thought of everlasting devastation and winter can never leave him, both by nature and circumstance. The ‘blossom’ here is simultaneously jejune and apocalyptic.

“In its simplicity and sincerity, the title (which I borrowed from the artist), One Thing at a Time, and, by implication, the book, wants to describe experiences that I imagine were not dissimilar to those of the great seventeenth-century Edo period poet, Matsuo Basho, when it is said, perhaps somewhat apocryphally, he lived in a small house or hut in the northeastern hills of Kyoto Prefecture. Because this title (and the concept behind it) embodied the spirit of his work as an artist, I invited Abraham David Christian, who has, for as long as I can remember, lived part of the year in Japan, as well Dusseldorf and New York City, to do the abstract or analogical drawings, some even exquisitely and daringly illustrative, for this book of poems. Although I have never visited David’s small cottage in Hayama, pictures of it are evocative of Thoreau’s cabin on Walden Pond, and Basho’s modest dwelling (Basho-an) in the northeast hills of Kyoto.

“In the course of preparing the exhibition, the publisher-gallerist, Susanne Albrecht, in Berlin, wrote: ‘There is a vivid relationship between the drawings and the poems. The drawings could be images that reflect the meaning of the poems and they could be read as characters of an archaic language, thus giving the poetry the atmosphere of an oracle, of words and wisdom from a very old time. Now you have not only time, but also space in the book’.

“In this world of Pop culture, where the American ethos has unfortunately become a global reality, it was not that I wasn’t tempted to use as the book’s title, Apocalypse and Love or Girls Giggling Beneath the A-Bomb Dome. The former, because it made an ever so subtle allusion to Alain Resnais’s great film, Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959); the latter, to distance myself, in a Brechtian manner, from a topic still too painful to address directly – the former (title) obviously being ultimately too facetious and lacking sufficient gravitas, at least for me. The common idiom, ‘One Thing at a Time’, on the other hand, while facile to an extreme, catches at something that goes against the very grain of our Age of multi-tasking and social media. In the end, for me, it captures the ‘space between our thoughts’; it is about slowing things down long enough to actually experience them, if only in parts or as a partial reality.”

Oracle Bones: Poems 2007

by Richard Milazzo.

First edition paperback: January 2018.

Designed by Richard Milazzo.

88 pages, with a color cover reproducing a photograph by Joel Fisher,

35 original black and white photographs by Joel Fisher,

a black and white photograph of the author on the frontispiece by Joy L. Glass,

Deadwood Hotel, Deadwood, South Dakota, February 2008,

a preface by the author and a note by the artist.

7.5 x 4.5 in., printed, sewn and bound in Savignano sul Panaro,Italy.

ISBN: 1-893207-42-0.

ISBN: 978-1-893207-42-4.

Published by Tsukuda Island Press

240-0112, Kanagawa Prefecture Miura-gun,

Hayama-machi horiuchi 50, Japan.

About Oracle Poems: Poems 2007, the author, Richard Milazzo, writes: “It is a book I wrote ten years ago, but only now do I feel comfortable releasing it. Oddly enough, it is a book written mostly in the United States, New York City, to be exact, London and Paris, with forays into Montana, Wyoming, and Utah. ‘Oddly’, because so many of my current travels bring me to Southeast Asia and the Far East, especially. But when I invited Joel Fisher to ‘illustrate’ this book, I knew, of course, that he had been living in Vermont, but also in England and France, and, I found out later, in Germany, as well. So, in this regard, I thought there might or should be some consanguinity in terms of place or geography. Not that this is a necessary criterion to collaborate, but I did want to construct or see if there was a connection.

“Having said this, I was also only partially surprised to discover how the photographs by Joel Fisher seemed to have an approach-avoidance relationship with the poems. Or, to put this another way, they seem to generate a dissonant balance. Joel puts it this way: ‘I have been trying to get a sense of the space and silence in the poems. My work as I see it is being sure that the book’s configuration also works emotionally (and sometimes unexpectedly) between the two [the poems and the photographs]. Some images reinforce the poems, others send thoughts in a parallel direction, some superimpose ideas and textures like a duet’ [October 31, 2017].

“The source of Fisher’s photographic images, like the source of his sculptures, is noteworthy. For a period of time, when he was photographing his installations or documenting his sculptures and found that there were several shots left in the roll of film, he would shoot arbitrarily whatever was around him, just to finish off the roll. This ‘automatic’, or less conscious decision-making process, allowed him to capture almost a Surrealistic dimension or the more unconscious or latent content of the visible world, at least as he was experiencing it, making what was, in effect, less present or invisible or less noticeable more prominent. Strangely, the dissonant rapport between the poems and the photographs also serves, in a similar way, to underscore the less extrinsic features of both the poems and the photographs. In the end, this process, and its various permutations, enable us to experience or see in some small way what is less visible or more invisible in perception or within a given perception.

“The title of the book, Oracle Bones, alludes to an ancient (Roman, I believe) method of prophesizing the future, casting the bones of a creature like a pair of die or a game of Pick-up Sticks and reading our fate in its seemingly chance configurations.”

Night Song of the Cicadas:

Poems of South Korea, Japan, Vietnam, Cambodia, 2017

by Richard Milazzo.

First edition paperback: August 2018.

Designed by Richard Milazzo.

144 pages, with a gatefold color cover reproducing a photograph

of Ap Bac, Vietnam, rephotographed by the author,

Ap Bac Museum, Vietnam, Ap Bac, August 1, 2017.

Frontispiece: a black and white photograph by Richard Milazzo,

Self-Portrait, Seoul, South Korea, July 10, 2017.

52 original drawings created for the book by Joel Fisher

with an introduction by the author and a note by the artist.

9.25 x 6.5 in., printed, sewn and bound in Savignano sul Panaro,Italy.

ISBN: 1-893207-43-9.

ISBN: 978-1-893207-43-1.

Published by Galerie Albrecht, Berlin, Germany, 2018,

Why these drawings with these poems; or, conversely, why these poems with these drawings, are good questions, given that this book of poems by Richard Milazzo, Night Song of the Cicadas: Poems of South Korea, Japan, Vietnam, Cambodia, 2017, is doing double-duty as the catalogue for an exhibition of Joel Fisher’s 52 drawings and several sculptures at Galerie Albrecht in Berlin, from August 31 to October 2018.

What Fisher provides here as illustrations for this book of poems are ink drawings as shadows and as the shadows of shadows – their faint, barely visible doubles in pencil –, based on photographs of stains found in the streets of Paris, which together constitute “an alphabet of silence allowing for a parallel world of experience, where enunciation occurs as a form of pre-articulation, neither skewing interpretation nor interfering with the imagery of the adjacent poems.”

Still we must ask, what is the common ground they share? Much in the same way Fisher arbitrarily photographed the stains left by rain or other sources in Paris, seeing in their shapes the potential for drawings and sculptural forms, the author traveled from place to place in the Asian world – South Korea, Japan, Vietnam, Cambodia –, encountering and recording various points of interest, making observations, collecting impressions, that might later, back in his hotel room, precipitate something more than spurts of inspiration or single lines, inspiring perhaps the briefest of stories, steeped in the pathos of the human condition.

The fact that the poems find their analogue in Fisher’s Agents, and that some of his drawings look like cicadas, or, at least, creatural, is significant. On the face of nature, do we not leave the stain of human existence? And does not Nature, in its turn, leave its mark on us? Is Nature not the ultimate source of agency and the ultimate agent? Do we not comprise, despite all our pretensions and affectations, a reciprocal orgiastic miasm, with seemingly little rhyme or reason, endowed merely, like an insect, with the winding, groping tentacles and antennae of ever-waning, entropic perceptions? For many, the soul has been supplanted by the exigencies, the agency, of human existence. The poems merely tell the stories of these Agents, whether they are found in the streets of Paris, Seoul, Fukuoka, Saigon, or Phnom Penh. And perhaps they, in turn, reflect reciprocably but inadvertently the creatures or the stories of the creatures encountered in the Night Song[s]. Agents that are, no matter how amorphous or ellusive, no matter how delicate or horrific, always steadily mortal in every instance, in their ever-shifting modalities.

This is, perhaps, what these louche poems and dissolute drawings have in common. On a purely visceral or intuitive level – hardly analytical or diagnostic –, there was the sudden realization that perhaps the creatures populating Fisher’s drawings constitute subliminal embodiments of the “cicadas” in the book, creatures that are most certainly abstract but also undeniably mimetic. When the author asked the artist about this possibility, he said that he had kept the drawings in a file entitled Night Songs. Most of the the Agents do, indeed, feel creatural, not that the subjects of the poems, with a few exceptions, are literally about cicadas. But there were fields outside the author’s hotel windows, no matter how high up, and nights in South Korea, in which the sound of the cicadas “became so loud, it almost became unbearable, even gruesome.”